Understanding Inguinal Hernias is not easy. The anatomy in the groin region, is complex, and even for the surgical resident in training, has a three dimensional nature that takes years to understand. The anatomy begins at the level of the umbilicus (belly button) and continues down to the groin crease (the line created by the junction of the leg and the torso). Within this area, there is what is known as the Inguinal Canal, a tube which runs from the inside of the abdominal wall to the outside, in an oblique fashion.

This tube exists because of fetal development in the womb; during this time, the testicle travels from the inside of the abdominal cavity, through the wall, to the outside and down to the scrotum. The canal does not fully close down, as the testicle remains attached to the Vas Deferens, nerve, artery and vein, all known as the Spermatic Cord. In females, there are analogous structures, and the Round Ligament corresponds to the male Spermatic Cord.

These structures are what remain in the Inguinal Canal. If the canal closes around these structures and forms a tight seal, there is no hernia. However, if the canal does not form a tight seal, and remains somewhat open, an Inguinal Hernia occurs. The opening is a Hernia, and structures such as fat, intestine, or intraabdominal organs may “herniate” through this canal. If the opening is large enough, the patient will see and feel a bulge in the groin area. Sometimes the opening is not fully formed, but a significant weakness exists. After a certain amount of time and pressure, the weakness becomes an opening; hence the reason why so many people experience the sensation of a “pop” during a cough, sneeze, or any activity which is raising the intra-abdominal pressure (sports or work-outs). The last remnants of the abdominal wall structure give way, and the opening enlarges enough for something to herniate through.

REPAIRING THE INGUINAL HERNIA

Inguinal Hernia repairs used to be performed by pulling the edges of the opening together, and sewing them with suture material. Repairs such as the Bassini or Shouldice were used. Over the last several decades, however, surgeons have used a mesh, usually made of polypropylene, a nylon derivative, to patch the opening, rather than pull the edges together. With some exceptions, the data has consistently shown that mesh gives a superior repair in terms of recurrence. The current standard of care in most circumstances is to repair Inguinal Hernias with mesh. The most basic reason for this is simply mechanical; the tissue edges which are pulled together are under significant tension, and often times tear apart over time, despite sutures.

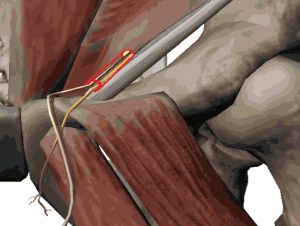

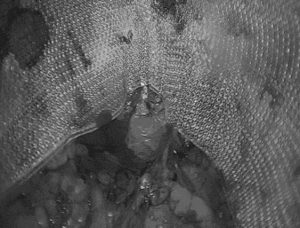

The two current methods of mesh repair are Open (Lichtenstein) Repair, and Laparoscopic (Minimally Invasive) Repair. The Open method begins with an incision in the skin, in the inguinal region, and a further incision in the External Oblique Fascia, which exposes the Inguinal Canal, and the hernia opening. A mesh is used to patch the opening, and held into place with sutures or tacks. The Laparoscopic Technique uses small puncture sites to introduce thin instruments into the area behind the abdominal wall. The repair is done from behind the defect, using a mesh which lays over the defect with a fairly substantial overlap over healthy tissue. In addition to fixing the actual opening, the mesh also covers other potential hernia sites such as the femoral canal or direct inguinal hernia space. Recovery time for the Laparoscopic Repair is usually shorter, given the smaller incisions, and in our practice, has a Recurrence Rate ¼ of the published standard 2% rate.

Posted on behalf of

133 E 58th St Suite 703

New York, NY 10022

Phone: (212) 628-8771

Email: frontdesk@coresurgicalmd.com

Monday - Thursday: 9:00AM to 5:00PMFriday: 9:00AM to 4:00PM

Saturday - Sunday: Closed